The complex and fascinating kingdom of fungi encompasses a diverse range of organisms, each with unique structural features and functions. The study of fungal anatomy reveals essential insights into their ecological roles, physiological processes, and potential applications in biotechnology and medicine. This article delves into the intricate structure of fungi, elucidating the various components that contribute to their unique biological characteristics.

The mycelium, fruiting bodies, and cellular structures form the fundamental framework of fungi, each element playing a pivotal role in their survival and functionality.

Mycelium: The Hidden Network of Fungi

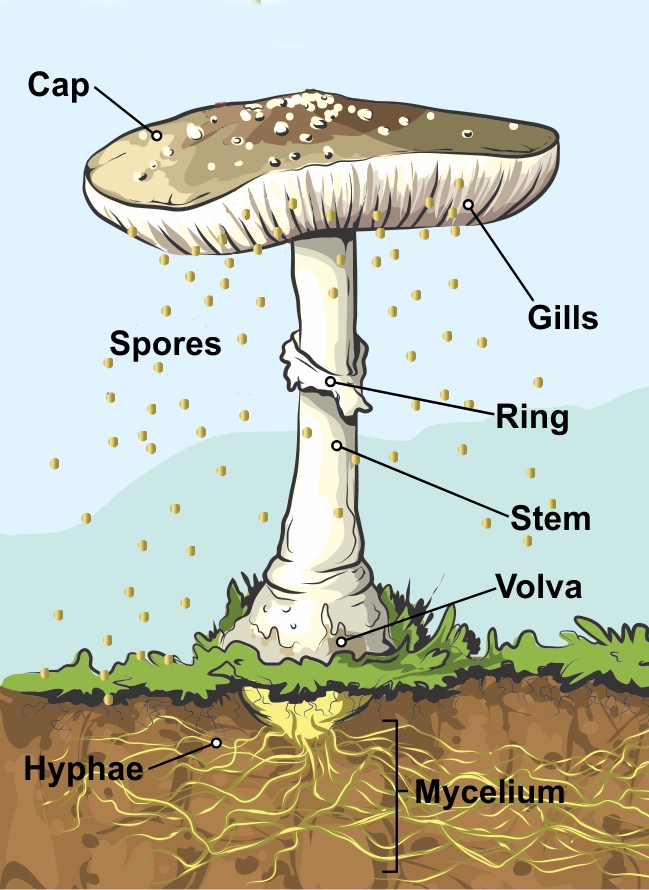

Mycelium constitutes the primary vegetative structure of fungi, formed by a network of filamentous hyphae. These hyphae are elongated, thread-like cells that extend through the substrate, forming a vast web of interconnections. The hyphal structure not only increases the surface area for nutrient absorption but also facilitates efficient resource distribution across the fungal organism.

One of the remarkable attributes of mycelium is its ability to form symbiotic relationships with other organisms. In mycorrhizal associations, for example, fungal hyphae intertwine with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake, particularly phosphorus, while providing carbohydrates in return. This mutualistic interaction is crucial for the health of terrestrial ecosystems, supporting plant growth and enhancing soil fertility.

Furthermore, mycelium serves as a mechanism for vegetative reproduction. In many fungi, hyphal fragments can break apart and establish new colonies, enabling fungi to invade new habitats and adapt to changing environmental conditions. The mycelial network also plays a vital role in decomposition, breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem.

Fruiting Bodies: The Reproductive Marvels

The fruiting body, or sporophore, is the visible and often intricate structure of fungi that emerges from the mycelial network. This reproductive organ is responsible for spore production and dispersion, vital for the propagation of fungal species. The morphology of fruiting bodies is remarkably diverse, encompassing forms such as mushrooms, puffballs, and shelf fungi, each adapted to specific ecological niches.

Fruiting bodies typically consist of a stipe (stem), pileus (cap), and gills or pores, which are critical for spore dispersal. The gills or pores expose large surface areas, maximizing spore release into the surrounding environment. Spores, which are haploid reproductive units, can be dispersed by wind, water, or animal activity, facilitating colonization of new substrates. The mechanisms of spore dispersal exemplify the evolutionary adaptations fungi have developed to survive and thrive in various habitats.

Additionally, environmental factors play a significant role in fruiting body formation. Conditions such as humidity, temperature, and substrate availability can trigger the transition from the mycelial phase to fruiting body development. This adaptability underscores the resilience of fungi, enabling them to flourish in variable environments.

Cellular Structure: The Building Blocks of Fungal Life

At the cellular level, fungi exhibit distinct structural characteristics that differentiate them from plants, animals, and bacteria. The fungal cell wall, primarily composed of chitin, provides structural integrity and protection against environmental stressors. Chitin, a polysaccharide also found in the exoskeletons of arthropods, endows fungi with rigidity while maintaining the necessary flexibility for growth.

In addition to the rigid cell wall, fungal cells contain unique organelles essential for metabolic processes. Mitochondria, responsible for energy production through cellular respiration, are abundant in fungal cells, reflecting their high metabolic demands. Furthermore, the presence of vacuoles supports intracellular storage and homeostasis, allowing fungi to regulate internal conditions effectively.

Another noteworthy feature of fungal cells is the presence of septa, or cross-walls, within hyphae. These septa compartmentalize the hyphae, allowing for efficient transport of nutrients and organelles, while also providing a degree of structural integrity. In some fungi, septa are perforated, permitting cytoplasmic streaming and communication between adjacent cells, which is crucial for coordinated growth and response to environmental stimuli.

Metabolic Diversity: The Functional Relevance of Structure

The structural attributes of fungi are inherently linked to their metabolic capabilities. Fungi are heterotrophic organisms, meaning they derive their nutrients from organic matter. This distinctive mode of nutrition is facilitated by their intricate hyphal structure, which maximizes surface area for absorption, allowing them to break down complex organic compounds through enzymatic processes.

Through the secretion of extracellular enzymes, fungi can decompose various substrates, including cellulose, lignin, and proteins. This ecological role as decomposers is vital to nutrient cycling in ecosystems, enabling the breakdown of dead organic material and the release of essential nutrients back into the soil. In doing so, fungi contribute to the maintenance of soil health and fertility, supporting plant communities and overall biodiversity.

The metabolic diversity observed among fungi is also noteworthy. Some fungi engage in saprophytic lifestyles, thriving on decaying organic matter, while others exhibit parasitic tendencies, deriving nutrients from living hosts. Mycoparasitism, in which one fungal species preys on another, highlights the competitive dynamics within fungal communities and the intricate relationships that evolve in natural ecosystems.

Fungal Biotechnological Applications: Harnessing Structure for Innovation

Understanding the structure and function of fungi has significant implications for biotechnology and medicine. The mycelial network’s capacity for biodegradation has garnered attention for its potential applications in waste management and bioremediation. Fungi can metabolize a variety of pollutants, including heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbons, making them pivotal agents in environmental cleanup efforts.

Moreover, fungi hold promise in the production of biofuels, enzymes, and pharmaceuticals. The unique properties of fungal enzymes, such as cellulases and ligninases, can be harnessed for industrial processes, enhancing the efficiency of biomass conversion for biofuel production. Additionally, various fungi are sources of bioactive compounds, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents.

The ongoing research into fungal structure and function continues to unveil novel applications, emphasizing the importance of this remarkable kingdom in advancing scientific and technological frontiers.

Conclusion

The structure of fungi, encompassing mycelium, fruiting bodies, and cellular components, reveals the complexity and adaptability inherent within this kingdom. From their critical roles in nutrient cycling to their potential applications in biotechnology, fungi represent a paradigm of ecological and evolutionary innovation. Continued exploration of their structural characteristics will undoubtedly advance our understanding of their biological significance and broaden the horizons of their practical utilizations.