Fungi are an enigmatic and vital group of organisms that inhabit nearly every ecological niche on Earth. Their distinctive biology and life cycles are essential not only for understanding ecological dynamics but also for appreciating the intricate relationships within various ecosystems. This article delves into fungal biology and their myriad modes of reproduction, examining the mechanisms that drive their life cycles.

The realm of fungi extends far beyond simple molds and mushrooms; it encompasses a staggering diversity that includes yeasts, molds, and the more complex multicellular structures seen in macrofungi. Fungi are classified under the Kingdom Fungi, separate from plants, animals, and bacteria. They exhibit unique cellular characteristics, including the presence of chitin in their cell walls, which distinguishes them from the cellulose in plants. Understanding their biology requires an exploration of their morphology, physiology, and reproductive strategies.

One of the most intriguing aspects of fungal biology is their reproductive strategies, which can be broadly categorized into asexual and sexual reproduction. This bimodal reproductive strategy allows fungi to thrive in various environments, adapting to challenges while maximizing their dispersal and survival opportunities. Below, we will dissect these mechanisms in greater detail, exploring the fascinating life cycle stages fungi undergo.

When considering asexual reproduction, fungi predominantly utilize spores to propagate themselves. Spores, the microscopic units of fungal reproduction, are resilient and can endure harsh environmental conditions. The generative phase of asexual reproduction is crucial for the rapid colonization of substrates. A notable method is budding, utilized by yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which produces new individuals by creating a small protrusion that eventually separates. This form of asexual reproduction is advantageous in nutrient-rich environments, where rapid growth and reproduction can outcompete potential rivals.

Another widespread asexual reproduction method is fragmentation, where mycelial networks break apart, allowing segments to grow into new fungal organisms. This method exemplifies the robustness of fungi. The filamentous structure of mycelium contributes to their resilience; mycelium can degrade organic material, taking on a pivotal role in nutrient cycling.

A fascinating yet often overlooked form of asexual reproduction is through spore formation. Fungal spore-producing structures can be remarkably ornate, serving as a testament to the diverse strategies fungi employ to secure their survival. Fungi can produce two primary types of spores: asexual conidia and sporangiospores. Conidia are produced in specialized structures called conidiophores and represent a powerful tool for dispersal, as they can be transported by wind, water, or other organisms. Sporangiospores, on the other hand, are enclosed in a sporangium and are released when environmental conditions are favorable.

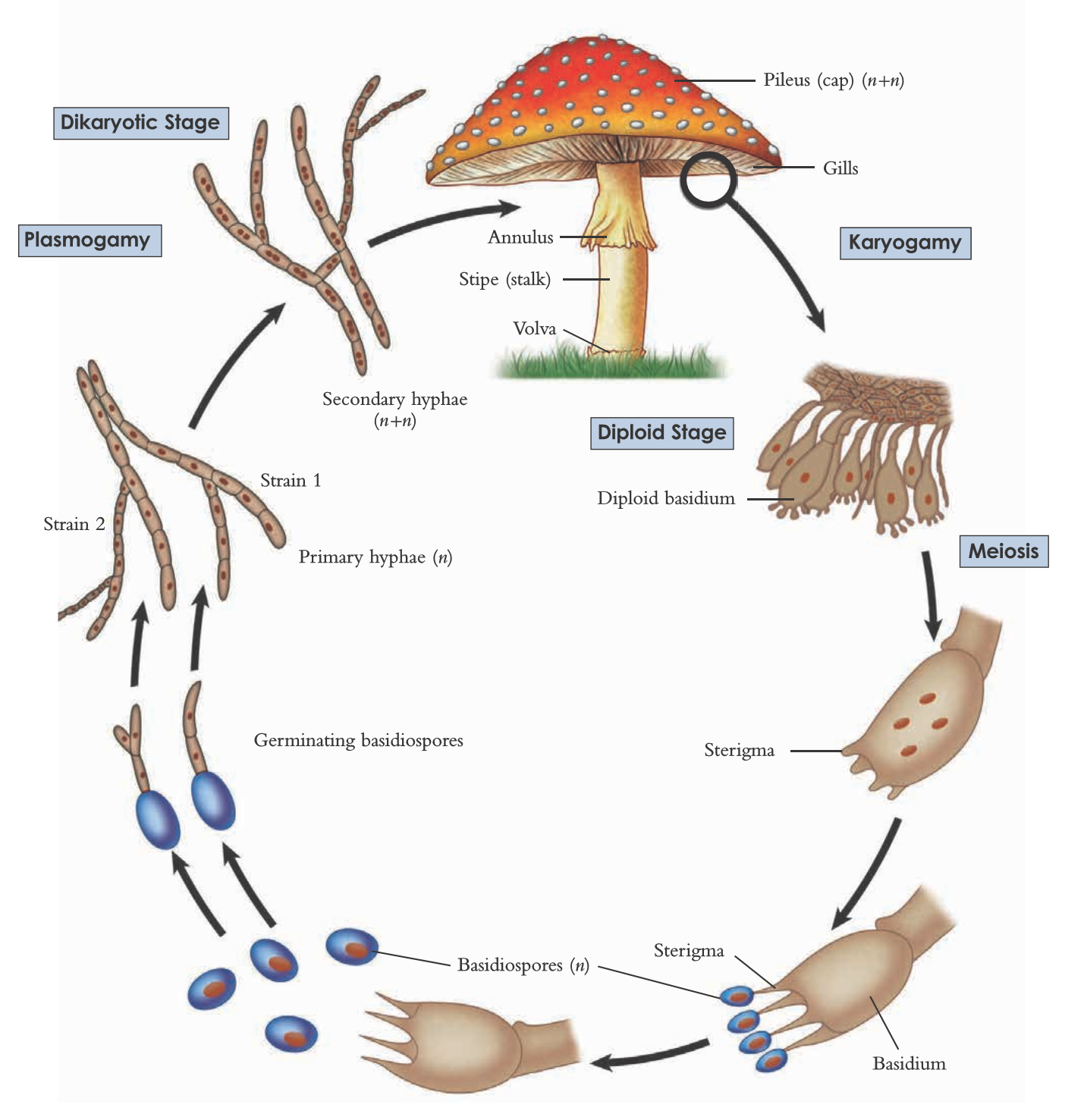

As we shift our focus toward sexual reproduction, we encounter an intricately choreographed process that adds layers of complexity to fungal life cycles. Sexual reproduction involves the fusion of specialized hyphal structures and may require the presence of compatible mating types, an essential prerequisite for successful fertilization. The process begins with the formation of specialized mating structures, typically referred to as gametangia. These structures house the nuclei that will ultimately fuse during the fertilization phase, leading to the formation of a zygote.

After fertilization occurs, the zygote undergoes karyogamy, a critical step where the haploid nuclei merge to form a diploid nucleus. This diploid stage is often ephemeral, with fungi rapidly transitioning back to a haploid state through meiosis. It is during this haploid phase that fungi produce sexual spores, a process that varies significantly among different classes of fungi.

Among the Ascomycetes, or sac fungi, sexual reproduction culminates in the formation of ascospores within sac-like structures known as asci. In contrast, Basidiomycetes, or club fungi, produce basidiospores on the surface of specialized structures called basidia. This meticulous organization exemplifies the evolutionary adaptations fungi have made throughout their fecund history.

The ecological and evolutionary implications of these reproductive strategies are profound. Fungi have established symbiotic relationships with plants, animals, and microorganisms, contributing to the foundation of many ecosystems. Mycorrhizal fungi, for instance, form crucial partnerships with plant roots, enhancing nutrient acquisition while providing plants with stability and protection from pathogens. This mutualistic interaction is a prime example of the interconnectedness of life forms and the role fungi play in sustaining biodiversity.

Yet the question remains, why have fungi evolved such diverse reproductive strategies? The answer lies in the unpredictable nature of their environments. Asexual reproduction permits rapid colonization of available resources, rapidly increasing population sizes, whereas sexual reproduction introduces genetic variability, a critical factor in adapting to changing conditions. This duality embodies the essence of survival, enabling fungi to not only endure but also thrive in diverse habitats.

Furthermore, the observation of environmental cues plays a significant role in dictating the choice between asexual and sexual reproduction. Factors such as nutrient availability, population density, and environmental stresses often trigger a switch in the reproductive strategy employed by the fungus, showcasing their remarkable adaptability.

Another captivating phenomenon associated with fungal reproduction is the phenomenon known as “fungal dormancy.” Under unfavorable conditions, many fungi can enter a dormant state, dramatically slowing their metabolic activity and allowing them to withstand periods of environmental stress. The ability to remain dormant and subsequently reactivate when conditions are favorable illustrates the resilience inherent to these organisms.

In summary, the realm of fungi is complex and multifaceted, characterized by unique biological features and intricate reproductive cycles. Exploring their asexual and sexual reproduction methods reveals not only how they inhabit various ecosystems but also highlights their essential roles in nutrient cycling and symbiotic relationships. Through adaptive strategies, fungi have withstood the test of time, weaving themselves into the fabric of life on Earth.

As you ponder the elegant designs of fungal biology and reproduction, it invites an intriguing contemplation: In what ways could understanding these processes further enhance our conservation efforts, agriculture, and comprehension of ecological interactions? The exquisite dance of spores, mycelium, and environmental factors continues to inspire inquiry into the rich tapestry of life dominated by these remarkable organisms.

References

1. N. J. Turner and N. L. O’Leary. “Fungi: Understanding Their Complex and Diverse Reproductive Strategies.” Mycology 12, no. 4 (2021): 243-261.

2. K. A. Duggan et al. “Adaptive Significance of Fungal Life Cycles: From Spores to Mycelium.” Fungal Biology Reviews 25, no. 1 (2022): 25-38.

3. D. S. Richards, “Ecological Relevance of Fungi: From Soil to Symbiosis.” Ecological Fungal Biology 19, no. 3 (2020): 101-115.