Introduction to Fungal Interactions

In the vast tapestry of life, fungi play a vital role not only as decomposers but also as intricate partners in a myriad of interactions with other microorganisms. While often overlooked, the realm of fungi is a vibrant ecosystem where these organisms demonstrate extraordinary capabilities in establishing symbiotic relationships, colonizing environments, and influencing their microbial neighbors. Understanding how fungi interact with bacteria, archaea, and even viruses unveils a fascinating story of cooperation, competition, and co-evolution, crucial for both ecological balance and biotechnological applications.

The Mosaic of Microbial Interactions

Fungi exist as part of larger microbial communities, interacting with various microorganisms in ways that can be broadly categorized into three types: mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism. Each of these interactions can have profound implications for ecosystem dynamics.

Mutualism: A Win-Win Situation

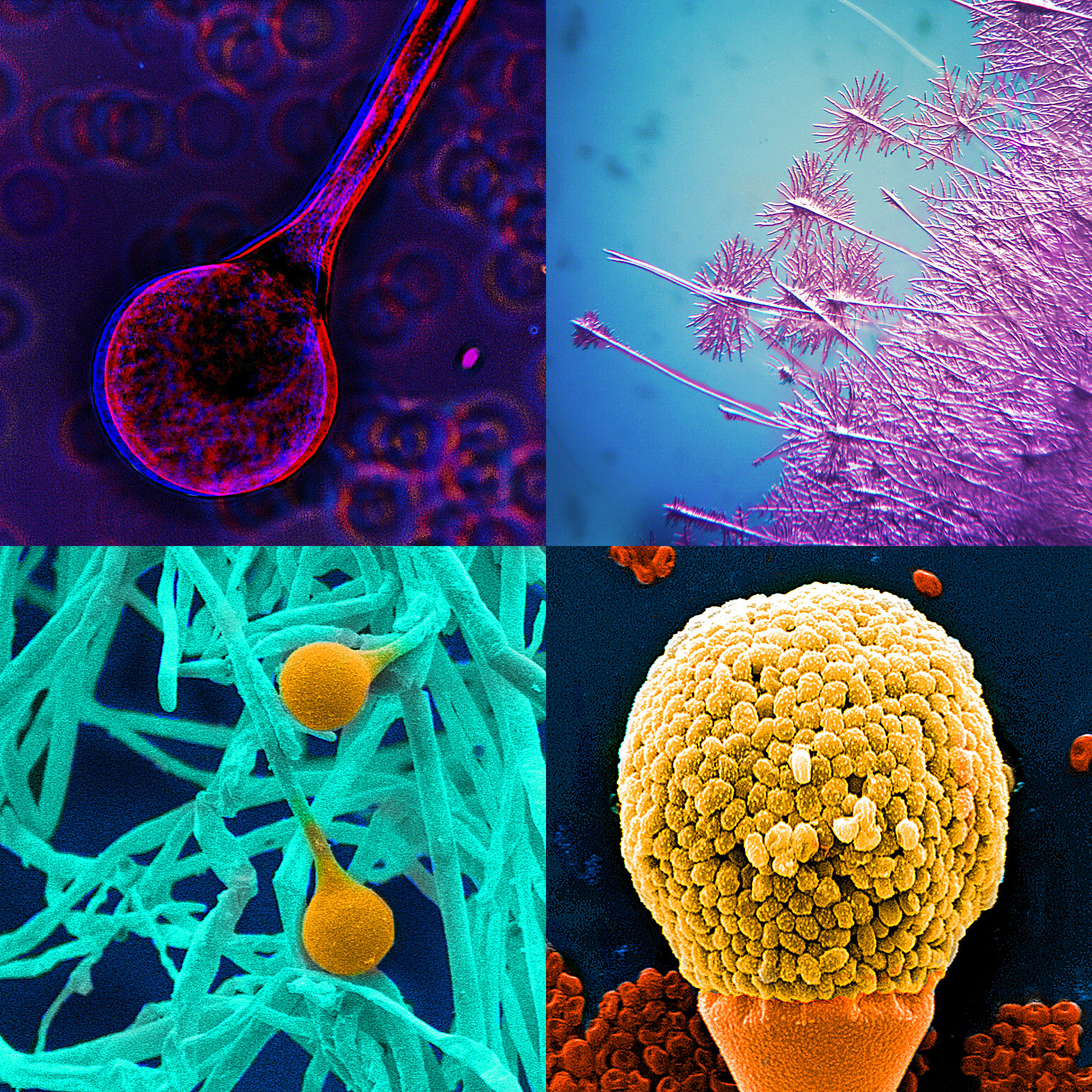

In mutualistic interactions, both fungi and their microbial partners derive benefits, creating symbiotic relationships that are critical for nutrient cycling and soil health. A prominent example is the mycorrhizal associations that fungi forge with the roots of vascular plants. This mutualism facilitates an exchange of nutrients; fungi extend their hyphal networks into the soil, enabling them to absorb water and essential minerals, particularly phosphorus. In return, fungi receive carbohydrates produced by the host plant through photosynthesis.

Notably, fungi also engage with bacteria in biogeochemical processes. Certain fungal species, such as Rhizopus, can form mutualistic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. This collaboration enhances soil fertility and promotes plant growth. The intimate interaction between fungi and bacteria often leads to enhanced biodegradation capabilities, revealing the potential of these partnerships in bioremediation efforts where pollutants are broken down into less harmful substances.

Commensalism: Shared Spaces

In commensal interactions, one organism benefits while the other remains largely unaffected. Fungi frequently inhabit environments already occupied by bacteria. For example, in decaying organic matter, fungi like Aspergillus and Penicillium can thrive alongside bacterial communities without inflicting harm. These assemblages can alter the dynamics of nutrient cycling, as fungal mycelium can digest complex organic materials, consequently releasing simpler compounds that bacteria can utilize.

Moreover, filamentous fungi may contribute to the overall microbial diversity of a habitat, indirectly benefiting bacteria by varying the microenvironment and improving the stability of nutrient availability. This nuanced interplay exemplifies how commensal relationships enhance ecological resilience by fostering diverse microbial ecosystems.

Parasitic Interactions: The Dark Side of Fungal Relationships

Parasitism showcases the more competitive and detrimental interactions where fungi exploit their microbial hosts for nutrition, often leading to the latter’s demise. Fungal pathogens can drastically impact microbial populations, agricultural crops, and even human health. A glaring example is the Ophiocordyceps unilateralis fungus, which infects ants, manipulating their behavior and ultimately leading to the host’s death. This interaction highlights a broader ecological theme: the balance of predator-prey dynamics at the microscopic level.

Fungi possess an array of biochemical strategies that enable them to suppress competing microorganisms. They produce secondary metabolites, such as antifungal and antibacterial compounds, to gain a competitive edge in their environment. Penicillium chrysogenum, for instance, produces penicillin, an antibiotic that selectively inhibits bacteria, showcasing how the evolutionary arms race shapes microbial interactions.

The Role of Biofilms: A Microbial City

Biofilms represent a unique aspect of microbial interactions, a complex community of microorganisms adhering to surfaces. Fungi are integral to biofilm formation, providing structure and stability. These surfaces can be natural (e.g., riverbeds) or artificial (e.g., medical implants). The synergistic cooperation between fungi and bacteria within biofilms results in enhanced nutrient acquisition, improved waste treatment, and increased resistance to environmental stresses.

Biofilms illustrate how fungi can serve as a foundation for multi-species interactions. The presence of fungal hyphae can alter the physical properties of the biofilm matrix, thereby modifying cell-to-cell communication among bacteria. This phenomenon often leads to a more diverse assemblage of microorganisms capable of tackling a broader range of environmental challenges. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing effective strategies for managing biofilm-associated infections in clinical settings.

Fungi as Environmental Engineers

The ability of fungi to interact with other microorganisms extends beyond direct relationships; they are environmental engineers that influence the habitat in which they reside. By decomposing organic matter, fungi release essential nutrients back into the ecosystem, driving the energy flow and nutrient cycling necessary for the survival of many cohabiting microorganisms.

Moreover, fungal activity modifies soil structure and composition, affecting water retention and aeration, critical factors for plant and microbe health alike. As some fungi degrade lignin and cellulose, they facilitate the breakdown of tough plant materials, thereby increasing the availability of simpler sugars for bacterial populations. This interaction exemplifies the interdependence of life forms in maintaining earth’s ecological balance.

The Future of Fungal-Microbial Interactions in Biotechnology

Scientific understanding of fungal-microbial interactions has expanded, revealing their immense potential for biotechnological innovations. Harnessing these interactions can lead to advancements in agriculture, medicine, and environmental management. For instance, incorporating mycorrhizal fungi into agricultural systems has shown promise in enhancing crop yield and resilience to pests and diseases.

Furthermore, as the demand for sustainable practices increases, the exploration of fungi’s roles in biodegradation and bioremediation has gained traction. Fungi can break down environmental pollutants, such as petroleum hydrocarbons and heavy metals, positioning them as essential players in the quest for cleaner ecosystems.

Additionally, the pharmacological potential of fungi has caught the attention of researchers, with antimicrobial and anticancer properties being explored extensively. Understanding how fungi interact with bacteria within these contexts could lead to novel therapeutic strategies against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Conclusion: Embracing the Fungal Frontier

As we venture further into the intricate world of fungi and their microbial companions, we unveil a nexus of interactions that are fundamental to life itself. Fungi are not merely passive components of their ecosystems; they are active players that shape microbial communities, influence nutrient cycles, and promote ecological stability. The myriad ways in which fungi interact with other microorganisms ultimately underscore the complexity and fragility of life on our planet. Recognizing these interconnections can foster a deeper appreciation for biodiversity and inspire future generations to explore and protect the microbial realms that sustain us all.