Fungi are often perceived as inconspicuous entities lurking beneath decaying leaves, yet their contributions to nutrient cycling in ecosystems are profound and multifaceted. They form an intricate web of biological functions vital to maintaining ecological stability. This article delves into how fungi orchestrate the recycling of nutrients, ensure soil health, and foster symbiotic relationships that enhance the biodiversity of ecosystems.

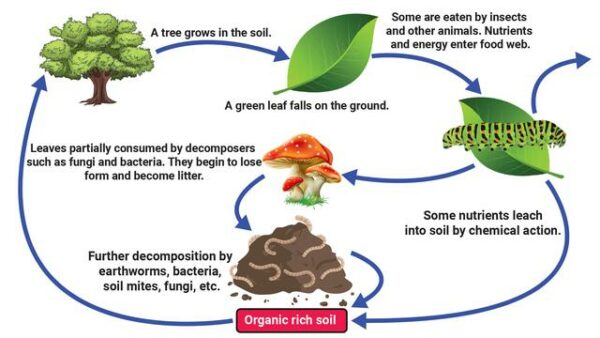

To appreciate the role of fungi in nutrient cycling, one must first understand the processes of decomposition and nutrient release. Decomposition, predominantly a biological process, transforms organic matter into simpler organic and inorganic substances. Fungi emerge as the key protagonists, adept at breaking down lignocellulosic materials. The enzymatic capabilities of fungi enable them to degrade complex molecules like cellulose and lignin—components that are notoriously resistant to decomposition. Through this enzymatic breakdown, fungi release essential nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus back into the soil, thus perpetuating a cycle of renewal and vitality.

Throughout their life cycle, fungi thrive in diverse environments, demonstrating their adaptability. They can be found in various forms, including saprotrophs, which decompose organic matter, and mycorrhizal fungi, that engage in mutualistic relationships with plant roots. This dynamic variability showcases their crucial role in the trophic interactions inherent in terrestrial ecosystems.

However, the question remains: How do fungi facilitate these processes? This exploration begins with their formidable structural adaptations.

Structural Adaptations: The Mycelium Network

Fungi possess a unique architecture, primarily comprised of a vast network of mycelium. This intricate filamentous structure allows them to maximize their surface area, optimizing nutrient absorption. Mycelium can extend for miles underground, exploring and colonizing substrates such as soil, wood, and decaying organic material. The extensive mycelial network enables fungi to interact with a multitude of substrates, ensuring efficient breakdown and nutrient retrieval.

Moreover, mycelium acts as a conduit for nutrient exchange not only for fungi themselves but also for surrounding flora. This subterranean network can be visualized akin to an underground information superhighway, coordinating exchanges of vital elements. By forming symbiotic associations with plant roots through structures known as arbuscules, mycorrhizal fungi enhance nutrient uptake, particularly of phosphorus, in exchange for carbohydrates produced by the host plant during photosynthesis. This symbiotic interaction exemplifies the complex interdependencies characterizing ecosystems.

But the story of nutrient cycling does not end with mere structural superiority; biochemical prowess plays a crucial role as well.

Biochemical Dynamics: Enzyme Production and Nutrient Liberation

Fungi are renowned for their ability to secrete an array of extracellular enzymes, which play a pivotal role in the degradation of organic matter. These enzymes, such as cellulases, ligninases, and proteases, enable fungi to break down various organic substrates, liberating nutrients in the process. This enzymatic arsenal allows fungi to inhabit niches that many other organisms cannot exploit, establishing them as primary decomposers in ecosystems.

The implications of this enzymatic activity reach far beyond mere nutrient release. Fungi catalyze various biogeochemical cycles, particularly the carbon and nitrogen cycles. As fungi decompose organic matter, they convert complex organic material into simpler forms that can be used by plants and other organisms. For instance, the decomposition of dead plant matter by fungi results in the release of carbon dioxide, which is then utilized by photosynthetic organisms to synthesize new organic material, thereby propagating the cycle.

Furthermore, fungi participate significantly in the nitrogen cycle through their relationship with various nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Certain fungi can harness atmospheric nitrogen, facilitating its conversion into a biologically available form for uptake by plants. This nitrogen-fixing capacity is essential in nitrogen-poor ecosystems, effectively enriching the soil and contributing to increased plant productivity.

Consider the consequences of the interplay between fungi, plants, and microorganisms: Without this synergy, many ecosystems would struggle to sustain themselves, teetering on the brink of nutritional inadequacy. This illustrates the intricate connectivity among the abiotic and biotic components of ecosystems.

Ecological Interdependencies: The Role of Fungi in Biodiversity

In addition to their biochemical and structural roles, fungi are essential for fostering biodiversity within ecosystems. Their ability to decompose organic matter creates habitats that support a myriad of microbial and animal life. By providing the foundational nutrients required for plant growth, fungi indirectly support herbivores, which, in turn, sustain higher trophic levels, including predators.

Indeed, the presence of diverse fungal communities can enhance ecosystem resilience. Research has demonstrated that ecosystems rich in fungal diversity are better equipped to withstand perturbations such as droughts, pest outbreaks, or invasive species. This diversity allows for multiple pathways of nutrient cycling, ensuring that if one pathway is disrupted, others can compensate, thus maintaining ecological balance.

Despite the evident benefits fungi provide, their contributions often go unnoticed—a phenomenon described as “the hidden half.” This notion challenges the reader to reconsider the significance of these often-overlooked organisms in ecological networks. How many other vital processes in our ecosystems are obscured from view? As fungi work diligently beneath our feet, they orchestrate a symphony of interconnected processes that sustain life on our planet.

Future Implications: Fungi and Ecosystem Management

Understanding the elegant interplay of fungi in nutrient cycling holds significant implications for ecosystem management and restoration efforts. As the effects of climate change and anthropogenic influences become increasingly apparent, the degradation of ecosystems calls for innovative management strategies focusing on biodiversity preservation. Incorporating fungal conservation measures into land management practices can enhance soil health and resilience, contributing to more sustainable agricultural practices and ecological restoration efforts.

For instance, incorporating mycorrhizal inoculation techniques in agricultural systems offers promising avenues to bolster plant growth and nutrient efficiency. Similarly, recognizing the importance of fungal diversity in forest management can provide insights into maintaining ecosystem integrity amid changing environmental conditions.

The ecological narrative is vast and intricate. As stewards of the Earth, it is incumbent upon us to recognize and appreciate the critical roles fungi play in maintaining the fabric of life across various ecosystems. Through education, restoration, and conservation, we can ensure that these essential organisms continue to thrive, captivating the imagination and underscoring our connection to the natural world.