Fungi represent a vast and intricate kingdom of life, encompassing a diverse range of organisms that are crucial to ecosystems, human health, and various industries. Understanding how to differentiate between various types of fungi involves examining their morphological, physiological, and genetic characteristics. This article delves into the methods employed in distinguishing diverse fungi, shedding light on their classification and significance.

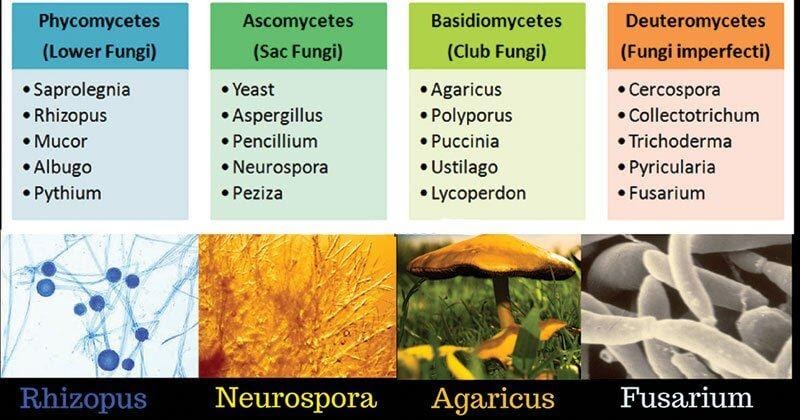

The Kingdom Fungi is typically categorized into several phyla, each comprising distinct classes, orders, families, genera, and species. Identifying fungi requires an appreciation of their structural and functional diversity. Common techniques employed include morphology, reproductive strategies, ecological roles, and molecular biology.

Understanding Fungal Morphology

The morphological traits of fungi provide critical clues for their identification. Observing characteristics such as texture, color, size, and shape can reveal much about the organism in question.

Macroscopic Characteristics

Macroscopic features are those observable without a microscope and include colony color, texture, and growth pattern. For instance, the surface texture may be dry, velvety, or moist. The appearance of fungal colonies can vary immensely, from the fluffy structures of *Aspergillus* species to the leathery consistency of *Ganoderma*. Observing these traits allows mycologists to categorize fungi into genera based on similarities.

Microscopic Characteristics

Microscopic examination reveals critical details that are essential for precise identification. Hyphae, the filamentous structures that make up the mycelium of fungi, vary in thickness, septation (presence of cross-walls), and branching patterns. For example, *Penicillium* features septate hyphae with dichotomous branching, while *Rhizopus* has coenocytic hyphae lacking septa. Additionally, reproductive structures (such as spores) offer a wealth of information. The morphology of spores—whether they are asexual (conidia) or sexual (ascospores and basidiospores)—can significantly influence taxonomic placement.

Reproductive Strategies: A Key to Identification

The reproductive methods employed by fungi can also serve as a distinguishing factor. Fungi reproduce both sexually and asexually, with each method exhibiting unique structures and stages.

Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction often occurs via the production of spores, which can be dispersed by air, water, or vectors. A notable example is the conidia produced by the *Aspergillus* genus. These conidia arise from specialized structures called conidiophores, which can vary in arrangement. In contrast, some fungi reproduce via fragmentation, where mycelial parts break off and form new individuals. This method is common among fungi like *Stachybotrys*.

Sexual Reproduction

Sexual reproduction in fungi typically involves the fusion of compatible haploid hyphae, leading to the formation of zygospores, ascospores, or basidiospores, depending on the phylum. For instance, the *Ascomycota* phylum employs asci to contain its spores, while the *Basidiomycota* produces basidia for its reproductive structures. Understanding these reproductive mechanisms aids in distinguishing between closely related species, particularly in taxonomically challenging groups.

Ecological Roles and Habitats

Fungi play multifaceted roles within ecosystems, including decomposers, mutualists, and pathogens. Their ecological niches often provide additional insights into their classification.

Decomposers and Saprophytes

As saprophytes, many fungi fulfill the essential role of decomposition. They break down organic matter, returning vital nutrients to the ecosystem. Common decomposer fungi include members of the *Mortierella* and *Trichoderma* genera, which thrive in decaying wood or leaf litter. The presence of certain saprotrophic fungi can indicate specific environmental conditions or substrate availability.

Mycorrhizal Fungi

Mycorrhizal fungi establish symbiotic relationships with plant roots, facilitating nutrient exchange. This form of mutualism is particularly evident in ectomycorrhizal fungi, which interact with trees. Identifying these fungi often involves analyzing their specific ecological associations and morphological features, such as the presence of specialized structures like arbuscules or vesicles in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Understanding these relationships enhances our comprehension of soil health and plant physiology.

Pathogenic Fungi

Some fungi engage in parasitism, causing diseases in plants and animals. Identifying pathogenic fungi involves recognizing morphological characteristics and the symptoms they produce. For instance, the *Fusarium* genus is known for its diverse group of plant pathogens, characterized by their mycelial growth and distinctive conidial forms. Knowledge of fungal pathogenesis is critical for agricultural management and disease control strategies.

Molecular Techniques in Fungal Differentiation

The advent of molecular biology has revolutionized the field of mycology, allowing for more precise differentiation of fungi through genetic analysis.

DNA Barcoding

DNA barcoding entails sequencing specific regions of the fungal genome, typically ribosomal RNA genes such as the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. This technique provides a genetic fingerprint, enabling accurate identification of fungi, including those morphologically similar. With the escalating number of described fungal species, molecular methods have become indispensable in phylogenetics and biodiversity assessments.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis utilizes DNA sequences to elucidate evolutionary relationships among fungal taxa. By employing techniques such as maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference, researchers can construct phylogenetic trees that reflect the evolutionary trajectory of specific groups of fungi. This genetic insight aids in understanding speciation events and the complexities of fungal evolution.

In summary, differentiating types of fungi necessitates an integration of various methodologies, encompassing morphological examinations, reproductive strategies, ecological understanding, and molecular techniques. As our comprehension of this intricate kingdom deepens, so does our ability to harness fungi’s potential in addressing environmental challenges, advancing medical therapeutics, and supporting agricultural sustainability.